From the Daughters Of the Republic of Texas Museum, Austin via the Dallas Morning News archives.

Compared to the dizzying array of communication vehicles that exist today, suffragist leaders had a limited number of options available for spreading the word about their campaign. So how did they get the job done?

They wrote letters. Lots and lots of letters.

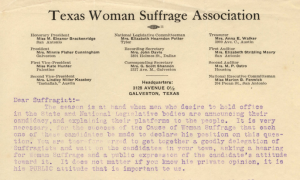

On the left: A communication from the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (a forerunner of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association) urging suffragists to pressure political candidates to declare a position on votes for women. Image from The University of Houston.

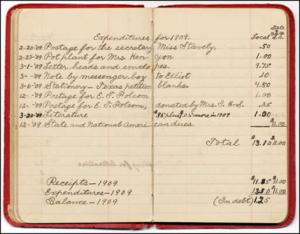

On the left: Expenditures from the 1909 Austin Woman Suffrage Association treasurer’s book reflect the importance of letter writing to the suffrage campaign. Image from the Austin Public Library.

Letter writing was a primary form of communication in the pre-digital age. But even by the basis of late 19th and early 20th century standards, suffragists took pen in hand with remarkable frequency, writing thousands upon thousands of letters to women friends, elected officials, newspaper editors, and each other in support of their cause. The spirit of this tactic lives on today, as women leaders employ email and postcard campaigns to get out the vote or mobilize efforts for public policy empowering women and girls.

They dressed in white.

On the left: From The Bullock Museum Digital Artifact Gallery.

Like their counterparts across the U.S., Texas suffragists would often demonstrate their solidarity by dressing in white for public events, a practice imported from the British suffrage movement. Even today, many women political candidates and other activists wear white as a tribute to the contributions of these pioneers for women’s rights. (Want to learn more? Visit the digital artifact gallery of the Bullock Museum, which offers an intriguing exhibit about suffrage fashion and other suffrage topics.)

They staged plays.

On the left: From the Erminia Thompson Folsom Collection, Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

To add an emotional appeal to their cause, suffragists staged plays and performed original music to reinforce the key messages of their campaign. Echoes of this tactic live on today, as women leaders leverage video, selfies, and live events like flash mobs to encourage voting and influence public policy related to women’s issues.

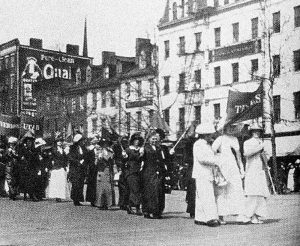

They mobilized in public.

Although Texas suffragists were somewhat less inclined to march or occupy relative to their counterparts in other regions, they did participate in national suffrage parades in New York or D.C., and they also held or participated in local parades and public awareness events, such as “Suffrage Day” at the Texas State Fair. See African American women’s role in advancing suffrage rights»

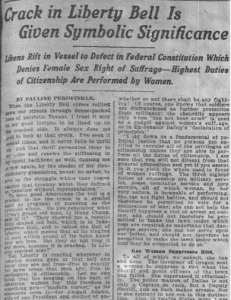

They authored articles and newspaper columns.

On the left: Article by Pauline Periwinkle, editor of the Dallas Morning News.

Texas suffrage leaders Minnie Fisher Cunningham, Jane McCallum, and Pauline Periwinkle are all example of suffragists noted for their authorship of articles and newspaper columns that made the case for equal voting rights and other issues important to women.

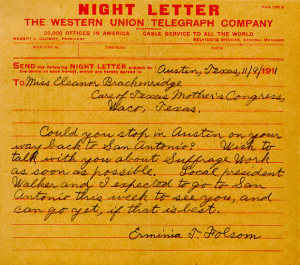

They sent telegrams.

On the left: Telegram to San Antonio suffrage leader Mary Eleanor Brackenridge. From the Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Since telegrams could be deployed faster than letters, suffragists used them as a way to quickly transact business or connect with each other—and they also used them for legislative advocacy. For a period during the special legislative session called after the impeachment of anti-suffragist governor James “Pa” Ferguson, suffragist leaders sent pro-suffrage telegrams from influential allies every 15 minutes to state legislators, which helped persuade legislators to allow women to vote in the 1918 primary election, the first major victory for the Texas suffrage movement.

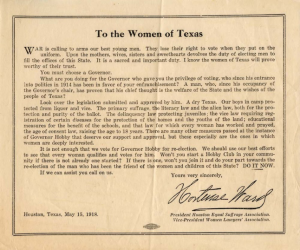

They supported pro-suffrage political candidates.

On the left: Open letter from the Houston Equal Suffrage Association urging Texas women to support William P. Hobby for governor. From The University of Houston Digital Library: Women’s Archives, Minnie Fisher Cunningham Papers.

Just like women activists of today, suffragist leaders rallied in support of political candidates who favored votes for women. Suffragist-sponsored “Hobby Clubs” and other pro-Hobby efforts helped secure victory for the Texas governor who would ultimately sign Texas’s first full suffrage bill.

Additional Reading:

“Impeached: The Removal of Texas Governor James E. Ferguson” by Jessica Brannon-Wranosky and Bruce A. Glasrud

“Citizens At Last: The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Texas” by Ellen C. Temple, Ruthe Winegarten and Judith N. McArthur

“Pauline Periwinkle and Progressive Reform in Dallas” by Jacquelyn Masur McElhaney