Travis County women register to vote. Image from the W.D. Hornaday Collection, Prints and Photographs Collection, Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

The moment: July 27, 1918

The place: Polling locations across Texas

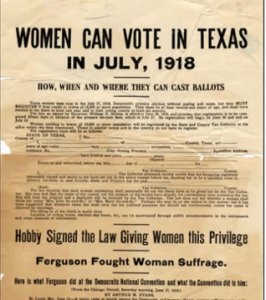

A watershed moment in the fight for votes for Texas women happened on March 26, 1918, when Governor William Hobby signed a bill giving women the right to vote in the Texas primary election.

The bill was passed during a special legislative session called after the impeachment of anti-suffrage Governor James “Pa” Ferguson, which suffragist leaders helped bring about. During the session, suffragist groups and their allies staged a petition drive that secured the signatures of a majority of legislative members, which led to the bill’s passage in both the Texas House and Senate.

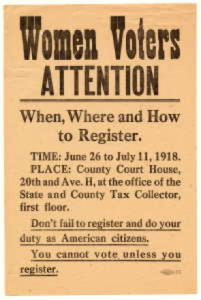

It was a thrilling victory for Texas women who had worked so hard to achieve equal voting rights—but there was little time to celebrate. The bill was passed within less than a month of the registration deadline for the primary election, which meant that suffrage leaders had to act fast. Through hastily-organized “citizenship schools” and information booths set up at department stores, courthouses and other public locales, suffrage groups and other organizations conducted a public education campaign and staged mock elections to educate women on the basics of election participation. Astonishingly, they managed to register an estimated 386,000 women in only 17 days.

On the left: Suffrage leaders had to work quickly to spread the word about Texas women’s opportunity to vote for the first time in history. Images from the From the Carey C. Shuart Women’s Archive & Research Collection at The University of Houston and the Austin Public Library.

It’s important to note that Texas law at this time permitted the practice of “white primaries”, a voter suppression tactic used throughout the South to keep African-Americans, Mexican Americans and other minorities away from the ballot box.

This meant that although many African-American women registered to vote in the historic primary, they were denied their rights on election day—even though many African-American women in Texas supported suffrage. In 1944, thanks to a lawsuit filed by the Houston branch of the NAACP (on behalf of a Houston dentist, Lonnie Smith) and the efforts of individual activists like Texas suffragist Christia Adair, the Supreme Court struck down white primaries and the practice came to an end, thus eliminating one of many barriers to full suffrage that persisted in Texas for decades.

Additional Reading:

“Primary Suffrage in Texas” – Austin Public Library